In-Between Worlds: Flood Adaptation in Marginalized Communities of Romania

The master's tools - blog by Ciprian Piraianu

30 September 2025

Can you imagine? Everything I worked for since I was sixteen to make a little house from scratch, it’s all gone.

As one of the defining challenges of the 21st century, climate change is intensifying extreme weather events such as floods and placing increasing pressure on communities to adapt. Yet not all communities are affected equally, and not all of them have the same resources to respond to disasters.

During the September 2024 floods in Galati, an eastern county of Romania bordering the Republic of Moldavia, rural localities suffered the most. The impact was severe: nearly 6000 households, along with livestock and crops, were destroyed, affecting 20,000 people across several localities. Six months after the floods, as part of my master’s thesis, I documented how marginalized communities in the “Global North” adapt when the nature they value and depend on turns against them.

Resisting? Disputing? the North-South Binary in Climate Justice

Climate justice has traditionally examined how industrialized Global North nations drive emissions while communities in the Global South, who contribute less, bear disproportionate harm. However, this process also happens at the micro-scale, within countries within the Global North. One of them is my home country, Romania.

While following the European Union guidelines for its climate adaptation strategy, the infrastructure, participation, and support are limited, especially in marginalized rural areas, where often its populations live in subsistence, at the margin of polluting industries. It feels like some of these smaller localities have been invisible after Romania’s transition to democracy in 1990. In the rush to achieve “European” standards in the cities, marginal rural residents and their households and small farms have been left economically, politically, and socially isolated, far from the “Northern” standards of modernity. The floods from September 2024 exposed these inequalities. Climate adaptation policies, such as the national flood management plans, stress technical measures like dikes, land planning, or climate modelling technology. Simultaneously, lived experiences of marginalized communities, intersectional vulnerabilities, and informal practices remained under-addressed in both policy and practice.

Structural Inequality and Intersecting Identities in Flood Vulnerability

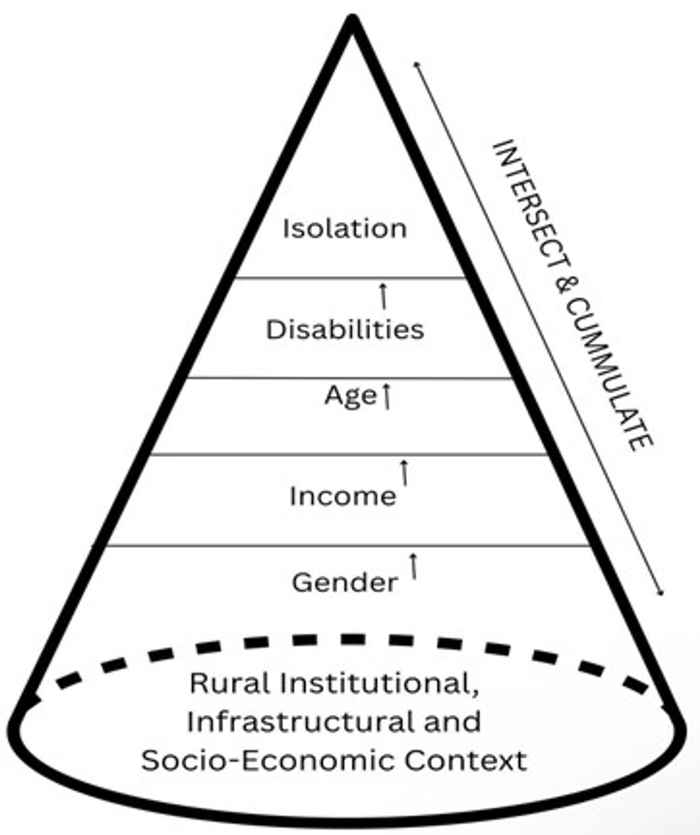

Vulnerability to flooding stems from both structural conditions and intersecting identities. Many rural areas face youth out-migration, limited infrastructure, few jobs, and small public budgets. Many locals have little formal education, survive from household agriculture and informal labor, and reside in self-built homes vulnerable to floods, some lacking documentation to access mandatory insurance or formal financing. These conditions erode adaptive capacity for households and officials alike, leading to tight budgets, limited know-how, and hard-to-navigate policies that make both access to support and on-the-ground implementation difficult.

Compounding and intersecting vulnerabilities in flood-affected areas of Galati County. The cone's base represents the shared marginal context, with each ascending layer illustrating an increase in overlapping vulnerabilities. The most affected were women with low income, advanced age, and disabilities, facing physical and social isolation.

After the 4th grade, my parents did not let me go to school anymore. There was work to do, and I had to raise my younger siblings. I was the best in the class; the teacher asked my father for several months to let me go back to school.

Gender roles

Besides the rural context, adaptation capacity was influenced by specific identities. Gender roles confined many women to household work, restricting their opportunities. As one female participant recalled:

Imagine. To be old, and you barely have a cold meal, it’s raining through the roof, outside it’s cold, you don’t have money for wood. The house is cracked, and the fence is falling apart. What are you still living for?

Age also played a key role, as elderly residents struggled with low incomes and poor health. In one of the interviews, the local priest shared with me the harsh situation of some elderly locals:

Finally, disabilities only deepened the sense of isolation. With no measures in place or infrastructure for those with disabilities, rising water turned homes into traps; for many, reaching an attic or escaping through a window was impossible. When roads and bridges failed, people with disabilities also lost access to essential services. Finally, disabilities only deepened the sense of isolation. With no measures in place or infrastructure for those with disabilities, rising water turned homes into traps; for many, reaching an attic or escaping through a window was impossible. When roads and bridges failed, people with disabilities also lost access to essential services.

After the flood, I stayed here (in the house) almost three days, without water. [...] I’m not crossing to the other side anymore.

One woman with mobility impairments described her situation after the bridge to the local store collapsed:

Formal and Informal Adaptation to Floods

Adaptation policies often neglect these infrastructural, economic, and social realities. Technocratic measures primarily benefit urban centers, while rural localities, though often at higher risk, are less equipped to face disasters and implement adaptation policies for the magnitude of the 2024 floods.

In the case of 2024 floods in Galati, this uneven context created challenges for both officials and community members.

You send people to ask for help. You see that I yell at you, and you yell back at someone else and announce them

Formal early-warning systems did not work or were not trusted, so mayors used police megaphones, door-to-door visits, or, as one mayor explained, mouth-to-mouth warnings:

Temporary housing units could not be transported through some of the narrow rural roads, forcing mayors to improvise, sometimes sheltering families on their own properties. The pressure of managing a life-threatening emergency situation without the necessary tools, amid damage to mayors’ own households, led to officials experiencing emotional and mental strain.

I had a psychological downfall... If I go into depth, if I talk about the night of the floods, I start crying. Because I relive the moment.

As one of the affected mayors admitted:

For community members, adapting meant restoring homes and household farms under social isolation and financial strain.

The state compensation of maximum 5000 euros was widely seen as unfit for purpose: insufficient rebuild a destroyed home, inequitably distributed because it was not proportionate to the level of damage, and rigid due to spending conditions that required buying specific goods like electronics. As one resident put it, “If someone has no home (anymore), why do they need electrical appliances? Where would they put them?”. Another community member highlighted the issue of distribution: “Many received compensation when the water barely passed behind their garden. (..) Let’s divide it among those more affected.” Faced with these constraints, people turned to donations, loans, remittances from relatives abroad, and, when necessary, selling the livestock they had left to piece their lives back together.

Immediately after the floods, big politicians came with television crews (…). Since then… everything has been quiet”. To cover the trust gap, the local priest emerged as an important actor, coordinating donations, distributing supplies, and bridging communication between the mayor and the community.

During this process, trust was decisive: due to past false alarms and the perceived dishonesty of officials, many ignored official warnings and compensation rules. One local explained that mistrust increased after the floods as the affected people were consulted only as a formality:

Localizing Policy and Research

After my thesis, I think I gained a complex understanding of how climate related events shape the realities of the local population, especially in marginalized areas of Romania. The findings from my research demonstrate that in climate adaptation, technocratic goals must be matched by equitable resource distribution, localized policies, and mental-health support. Budgets and flood-infrastructure investments should be equitably shared between cities and rural localities, while policies should consider the social, economic, and infrastructural realities of marginalized communities.

In this sense, I came to understand that post-disaster assessments should become an ongoing, transparent engagement to foster trust, and mental health support must be offered to both frontline officials and affected locals. This shift moves adaptation beyond technical fixes toward inclusive, justice-based models considering the lived realities of marginalized, rural communities in the Global North, enabling transformative measures over reactive, dislocated responses.