Clearing the Air: Environmental (In)Justice in Thailand’s Haze Crisis

The master's tools - blog by Erik van der Lee

21 August 2025

Each year, Chiang Mai’s skies are covered in a thick seasonal haze. While this is widely acknowledged as a health crisis, it is also a governance issue rooted in longstanding social and political inequalities. My thesis, based on fieldwork in Chiang Mai Province in Northern Thailand, explores how haze policies, specifically the Zero Burning Policy (ZBP), impact Indigenous highland communities and how these policies often obscure more systemic causes of pollution.

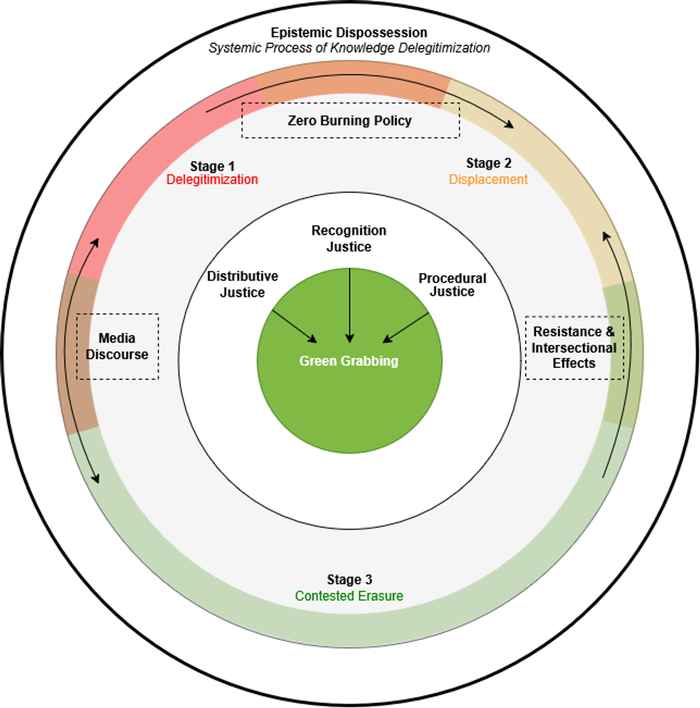

The ZBP does more than misidentify the source of pollution; it enables land appropriation by undermining the legitimacy of traditional practices. These processes are key enablers of what scholars describe as green grabbing, in which land is appropriated under the guise of environmental protection. Therefore, in my thesis, I propose a model of epistemic dispossession that traces how the delegitimization of Indigenous knowledge systems facilitates state-led interventions such as conservation zoning or park expansion.

The impacts of haze governance are not felt equally within Indigenous highland communities. Among other results in my fieldwork, I found that women play a central role in preserving seed varieties and managing rotational farming cycles. Certain seeds are only viable after fields have been cleared through controlled burning. When burn bans disrupt this ecological rhythm, women lose access to essential agricultural materials and knowledge spaces. This erosion of seed sovereignty not only affects harvests but also undermines their traditional roles.

While faced with the threat of criminalization, some households engage in ‘burning in the dark,’ continuing ancestral practices away from view and satellite hotspot detection. These acts of feigned compliance reflect quiet resistance to restrictive policies and are part of what James Scott described as ‘weapons of the weak’. This resilience, expressed through strategic adaptation and cultural continuity, is an essential part of the story. These communities do not passively accept the erasure of their practices. Rather, their strategies demonstrate that resistance persists even as knowledge is devalued.

Households without formal land titles are also especially vulnerable to enforcement. And younger generations, already at risk of cultural disconnection, are left with fewer means of understanding or continuing traditional land management.

However, there have been efforts to bridge this divide. A promising example is the FireD system, developed by Chiang Mai University in 2021, which allows villagers to register and carry out prescribed burns under controlled conditions. Although not without its flaws, this system was praised for its collaborative model and its potential to combine TEK with modern risk monitoring. Despite its demonstrated local success in Chiang Mai province, FireD was sidelined by top-down enforcement as the ZBP intensified in 2025.

Chiang Mai’s haze is not just a seasonal event but a political symptom of deeper structural injustices. Clean air is a basic right, yet current policies that marginalize Indigenous highland communities neither deliver justice nor solve the pollution problem. If we are serious about addressing the haze crisis, governance models that recognize the contributions of Indigenous highland communities are needed to confront the real drivers of pollution, and place justice at the center of environmental protection.